Taking a Scenic Route

Brennan K Peel

Nov 30, 2012

Do you know the landscape of your writing? If you painted your writing style, put acrylic to canvas, what would the image show? Nearly half a century ago, an English professor at Rice University published a book of essays ruminating on culture and writing in his native state. In the first of those essays, that teacher, Larry McMurtry, wrote that prose should resemble the landscape in which it's set. McMurtry--who of course went on to critical and commercial success, including winning a Pulitzer Prize in fiction--typically writes in a plainclothes prose that, he would argue, resembles the simple sparseness of his characters and their surroundings. "Prose, I believe must accord with the land," he writes in "Here's HUD in Your Eye," the first essay of 1986's In A Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas. Faulkner, whom he gives as an example, could write bramble-dense sentences because the style mirrors Yoknapatawpha's geography in northwestern Mississippi and the complex psyches of characters who live there. But for McMurtry, such lyrical flourishes would be overdone:A lyricism appropriate to the Southwest needs to be as clean as a bleached bone and as well-spaced as trees on the llano. The elements still dominate here, and a spare, elemental language, with now and then a touch of elegance, will suffice. We could probably use Mark Twain, but I doubt we're yet civilized enough to need a Henry James.

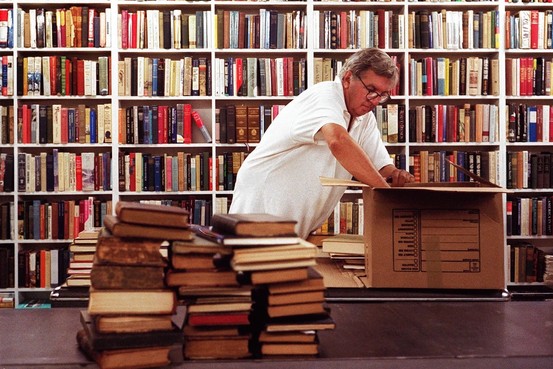

(McMurtry in his former Archer City, Texas bookstore, now liquidated)

You can argue whether that's a fair or even relevant condition to create or judge good writing. The way I read it is as a refashioning of that old advice to write what you know. That is, write not just what you know but in a style that proves it. In this claim McMurtry seems to assume that writers work with characters and in settings just outside the front door (which, ostensibly, means they'd be relatively easy to know).

For the most part, that's what McMurtry did--though out the front door of his childhood and later adult homes, not while he was in Houston or California. But what about others, those who write about people far, far away or (gasp!) in a world completely fabricated in the mind?

Of course some think that "writing what you know" is bunk. Annie Proulx (who won her own Pulitzer) said in a 1997 interview in The Atlantic that the oft-touted guidance "is the most tiresome and stupid advice that could possibly be given." Instead, she encouraged writers to write about what interests them and to use writing as a medium for growth and exploration.

But maybe Larry and Annie can both be right. (Side note: they worked together, sort of, when McMurtry, with Diana Ossana, adapted Proulx's story "Brokeback Mountain" for the screen. Here's the three of them discussing working together, in a 2005 article for New West.) Writing can resemble the landscapes around us while still probing for new information.

Here at Gulf Coast, for example, we're surrounded by myriad landscapes. We have outside our front doors the urban sprawl of the fourth-largest city in the US, replete with skyscrapers, crackhouses, suburban subdivisions. Houston-based writing could be stereotypically Texan, pointedly urbane, or comfortably (or uncomfortably) suburban.

(McMurtry in his former Archer City, Texas bookstore, now liquidated)

You can argue whether that's a fair or even relevant condition to create or judge good writing. The way I read it is as a refashioning of that old advice to write what you know. That is, write not just what you know but in a style that proves it. In this claim McMurtry seems to assume that writers work with characters and in settings just outside the front door (which, ostensibly, means they'd be relatively easy to know).

For the most part, that's what McMurtry did--though out the front door of his childhood and later adult homes, not while he was in Houston or California. But what about others, those who write about people far, far away or (gasp!) in a world completely fabricated in the mind?

Of course some think that "writing what you know" is bunk. Annie Proulx (who won her own Pulitzer) said in a 1997 interview in The Atlantic that the oft-touted guidance "is the most tiresome and stupid advice that could possibly be given." Instead, she encouraged writers to write about what interests them and to use writing as a medium for growth and exploration.

But maybe Larry and Annie can both be right. (Side note: they worked together, sort of, when McMurtry, with Diana Ossana, adapted Proulx's story "Brokeback Mountain" for the screen. Here's the three of them discussing working together, in a 2005 article for New West.) Writing can resemble the landscapes around us while still probing for new information.

Here at Gulf Coast, for example, we're surrounded by myriad landscapes. We have outside our front doors the urban sprawl of the fourth-largest city in the US, replete with skyscrapers, crackhouses, suburban subdivisions. Houston-based writing could be stereotypically Texan, pointedly urbane, or comfortably (or uncomfortably) suburban.

Yet even if stories set here, or at least written while living here, were to mimic their surroundings, what style should such writing take? What surroundings should be reflected? Should the prose be complex? Include 10-cent words? This is not a place as one-dimensional as McMurtry's hometown.

Surely writers of all stripes and backgrounds can find in such a city places and people unlike those they've known. Surely there is room to grow.

As you travel over the holiday season (or, instead, sit at home in your underwear thankful you're not dealing with holiday travelers), peek out your window and think of your writing and see if one resembles the other.

Yet even if stories set here, or at least written while living here, were to mimic their surroundings, what style should such writing take? What surroundings should be reflected? Should the prose be complex? Include 10-cent words? This is not a place as one-dimensional as McMurtry's hometown.

Surely writers of all stripes and backgrounds can find in such a city places and people unlike those they've known. Surely there is room to grow.

As you travel over the holiday season (or, instead, sit at home in your underwear thankful you're not dealing with holiday travelers), peek out your window and think of your writing and see if one resembles the other.

Comments (1)

AM:

Jan 05, 2013 at 09:31 PM

Awesome post!

Add a Comment